Killian Schurmann

Glass Studio

SCULPTURED AND ARCHITECTURAL ART IN GLASS

Diffusion of Light

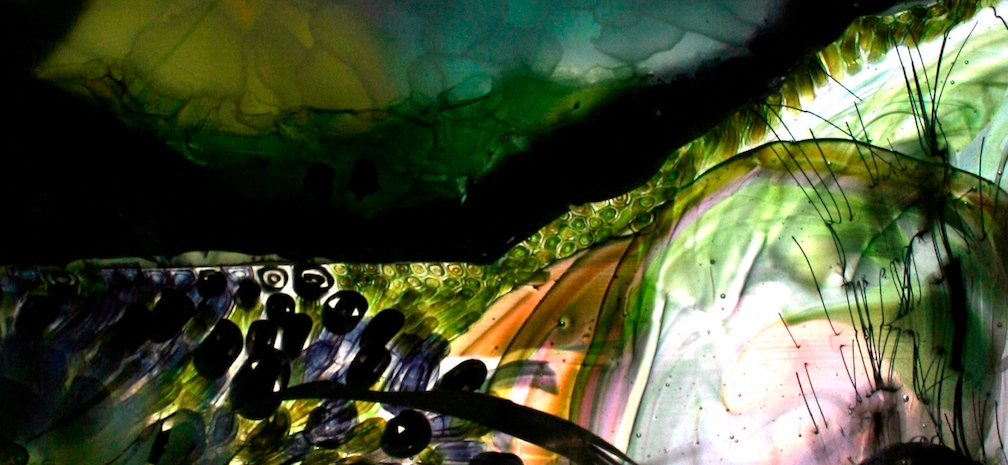

The minutiae of an urban landscape provides inspiration for the colours and textures fashioned by glass sculptor Killian Schurmann.

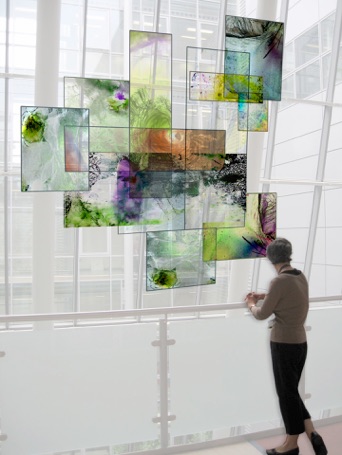

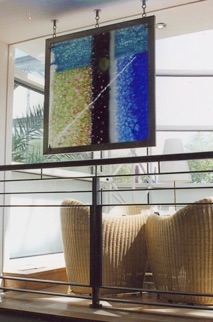

The incorporation of glass art in interior design, either as an installation or within the fabric of the building, brings an element of ongoing transformation to a static structure. Glass in all its manifestations is subject to change of light. Daylight transforms colour. Night brings reflection. The emphasis of the piece changes with the movement of the sun.

As with most projects that combine architecture and art, the strongest effects are attained when the applied artist works with the architect from the earliest stages. The glass artist Killian Schurmann feels that the projects that work best are those in which the collaboration with the architect begins at the planning stage. ‘The building is the architects’ artwork, so they should be involved in deciding what goes into the building and where it fits in,’ he explained. ‘If the artist working on the site isn’t involved from the earliest stages the work can appear like an afterthought to the building rather than an intrinsic part of its conceptual design.’

His most recent installation was for the decontamination unit in The Royal Hospital, Belfast. He had been asked to make a piece that referenced

the purpose of the building, and made a series of six glass panels, each about 1.10 x 90 centimetres, that rise like a ladder to the ceiling of the six metre high space. The colouring of the panels, which is dense at the lowest level and becomes progressively clearer as the installation rises, echoes the process of purification inherent in the building’s functionality.

Schurmann, who undertakes a variety of corporate and private commissions, has a particular interest in working in institutions, like schools and hospitals, where art is not always anticipated: ‘Because people aren’t expecting to find something there, they don’t feel that they have to understand it. They can just look at it and let it take them to another space, like staring into a rock pool.’ An ongoing installation, for the quiet room in the new Downpatrick Hospital, consists of five windows, all in blue, which fill the room with a dim underwater light. The idea behind this is that the patients can sit comfortably within the space without having to react to the other people in the room.

He is currently working with the children of a new build primary school in Blessington, according to a brief that requires him to involve the children from the outset. Although he usually works to a preconceived plan, the inspiration for this particular project will come from the process of working with the children. ‘I’m in there once a week with them. They’re modelling with clay and I’m transforming their work into glass. I’m teaching them how to find colours in nature rather than just by copying an image. I’m learning a lot about what I take for granted when I’m looking for colours because I have to explain it to the children.’ The final work will take the form of ten double-sided glass pieces, each the size and shape of the breeze blocks that they will replace at ten different locations in the school.

Concept, as well as colour, is an active element in his work. In 2000 he was approached by the directors of the Verbal Arts Centre in Derry. There is an ancient tradition in Ireland and Europe in which a precious object is buried in the foundation of a new building. The belief was that this would bring good luck and long life to the building. When the Verbal Arts Centre was under construction they invited contemporary writers in Ireland to make a gift of one page of a handwritten manuscript with a view to extending this tradition. Two hundred and twelve writers responded but, when the manuscripts came in they were so beautiful that the directors could not find it in their hearts to bury them. Schurmann came up with the concept of The Writer’s Wall – a glass sculpture of over two hundred stalactites, each encapsulating a manuscript. The manuscripts have been scanned and can be viewed on the touchscreen computer located beneath the sculpture.

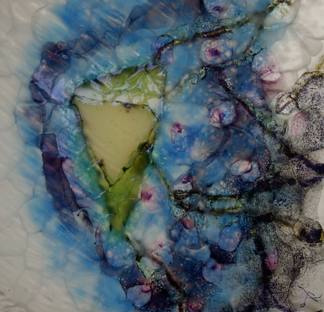

The opacity of his glass panels has the layered and muted quality of cloud cover with sudden bursts of colour, the surprise of lichen growing on stone or bright weeds flowering between cracks in the paving.

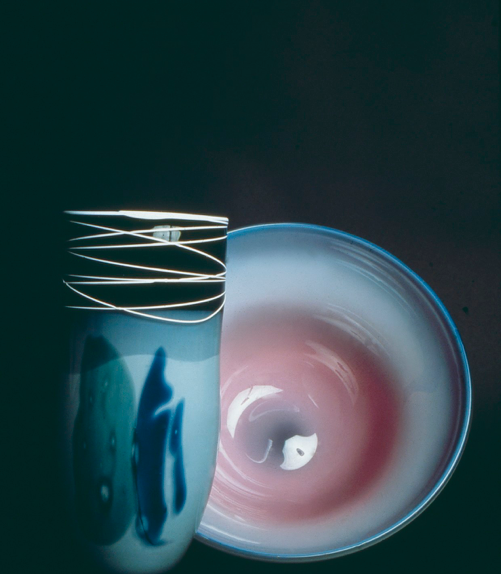

These pieces are just chapters in a long history of experimentation with glass. Schurmann trained as a scientific glass blower in Germany in 1980. For the next ten years he travelled as a journeyman, visiting studios throughout the world and exploring the field of glass art. Then he returned to Ireland. Throughout the nineties, between private commissions and exhibition work, he delved further into the art of glass, creating new colour compositions, textures, and ways of controlling the passage of light.

The opacity of his glass panels has the layered and muted quality of cloud cover with sudden bursts of colour, the surprise of lichen growing on stone or bright weeds flowering between cracks in the paving. The colours come from the nature of urban decay: the tidal scum of the Liffey, verging from green to black and darker grey; the mossy algae that grows around a persistent leak in a whitewashed wall. In terms of process the panels are fused – the glass is laid out in a kiln on a ceramic shelf and melted into a sheet – and devitrified, a process of very slow heating which gives them their white translucency. The colours are glass pigmentation, melted into the glass during the process. He often works with two panels of glass, one transparent and one opaque, fused together. When it’s dark outside it creates a reflection; in daylight the colours are transposed onto an opaque background. In Schurmann’s work, small specific memories of colour and movement – the way that colours overlap in the iris of an eye, the motion of someone running barefoot on hot sand – are captured within the glass. Sometimes, he says, he will remember colour combinations for years, more clearly than people’s names. Colour is trapped in memory, and then in glass, so that the end effect is of memory trapped in glass. And, because these memories relate to the way that colours combine in nature, they carry an essence of familiarity. They trigger an emotion, bring elusive memories to the surface, and then the light changes and you’ve lost it because the piece has been transformed into something else.

© Forma Interiors